Play of the Day

Posted: October 13, 2022 Filed under: art, Plays of the days Leave a commentI had the pleasure of profiling the work of Santa Barbara-based artist Alex Lukas in the newly published issue of LUM Art Magazine! Check it out here.

On the book

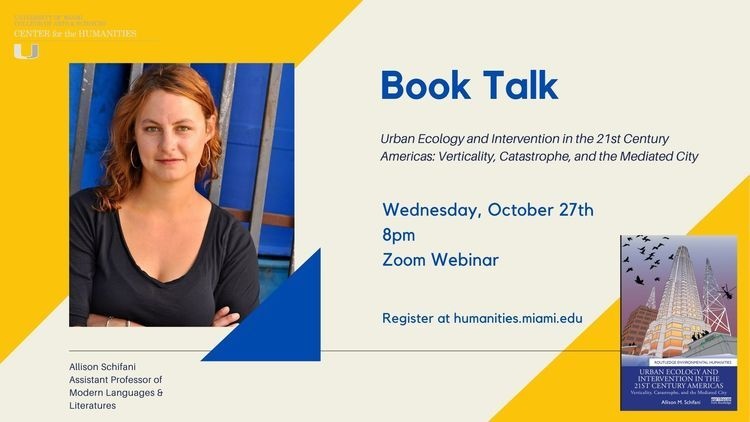

Posted: November 1, 2021 Filed under: art, Language and text, Plays of the days, Technology, Wandering in the city Leave a commentComrades! For those among you who might want to watch it, here is a recording of my book talk, offered virtually through the University of Miami’s Center for the Humanities.

Play of the Day

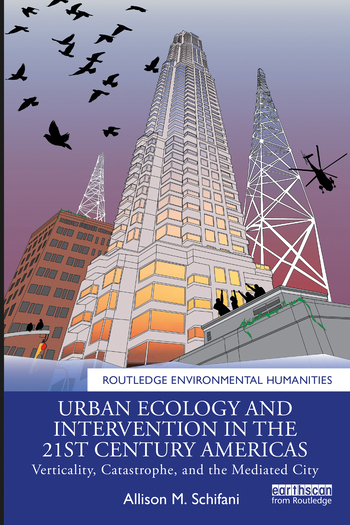

Posted: January 9, 2021 Filed under: art, Language and text, Plays of the days, Technology, Wandering in the city Leave a commentFriends, readers, comrades! It’s a new year! And while 2021 does not appear to be making any improvements on 2020, I can at the very least, and at long last, celebrate the publication of my first book: Urban Ecology and Intervention in the 21st Century Americas: Catastrophe, Verticality, and the Mediated City. Thanks very much to the folks at Routledge for helping usher it into the world. Thanks, too, to Martha Schulman, my copy editor. And to Kye Davolt for their beautiful cover art.

I also owe so much to the cities in which this book was written, both those depicted, described, and explored within it, and those places I called home along the way. This book is for Los Angeles, for Miami, for Buenos Aires, for Cleveland, and for Tucson. And for those urban denizens everywhere who strive for better worlds and better ways to live in them.

On 2020 and radical hope

Posted: June 12, 2020 Filed under: Wandering in the city Leave a comment 2020 will be remembered for many things, I imagine. Certainly for the global pandemic that has taken so many lives, has quieted cities and quashed economies, and that will likely continue to do so. Cases are rising in Florida, for example, and the newly re-opened stores, bars, and restaurants are surely both the cause of the uptick and a guarantee that the crisis will continue, without treatments or a vaccine, for the foreseeable future.

2020 will be remembered for many things, I imagine. Certainly for the global pandemic that has taken so many lives, has quieted cities and quashed economies, and that will likely continue to do so. Cases are rising in Florida, for example, and the newly re-opened stores, bars, and restaurants are surely both the cause of the uptick and a guarantee that the crisis will continue, without treatments or a vaccine, for the foreseeable future.

This year will be remembered for the increasing visibility of the impact of anthropogenic climate change: a burning Amazon, a burning Australia, a burning California, and what is shaping up to be a potentially devastating hurricane season for the Eastern seaboard.

It will also be remembered for a crushing global rise in nationalist populism, which saw strong-men like Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, and others leverage division and fear for their own benefit and at the expense of the very people they were tasked with leading and protecting.

It will be remembered, too, for the global uprising against white supremacy launched by the brutal murder of George Floyd at the hands of four Minneapolis police offers.

I walked in the streets of Miami in response to that murder, and the wretched 400 year-plus history of racist and racialized violence in the U.S. that preceded and predicted it, with thousands of my neighbors, my comrades, and my friends.

It was jarring to be among so, so many after months of isolation. Masked demonstrators all around me walked shoulder-to-shoulder. We yelled. We chanted. We mourned. We knelt. We cried. And unlike protestors across the nation and the world, at least when I marched, we were lucky. We were not, like so many, trapped, tear-gassed, pepper-sprayed, shot, shoved, and beaten by police.

But even if the police had come to surround us, I likely would have suffered a different fate than some of my comrades. I am the beneficiary of white supremacy. My safety, privilege, and wealth are, in this country, maintained at the express expense of my black and brown neighbors and friends. My life, by the standards of the systems under which we are currently governed, policed, and under which we work and learn, is deemed more valuable than theirs. This MUST end. BLACK LIVES MATTER. Period. Until we have fully dismantled the systems (governmental, juridical, disciplinary, educational, and economic) that refuse the absolute fact of the value of black lives, white people, like me, like (some of) you, will remain complicit in white supremacy, in racism, and in the systematic traumatization, devaluation, incarceration, and death of black and brown people.

The uprising, still ongoing, must go on. And it will. Let’s make it what we really remember about 2020. I want the deep and undeniable grief and rage, visible on the streets of cities everywhere– Minneapolis, Miami, Los Angeles, New York, Berlin, Cleveland, Paris, London, Albuquerque, Oakland and on, and on and on–to be marked in our histories as the necessary and final explosion against white supremacy. I want the grief and the rage to move through the world with such force that the devastation that launched it for so long is abolished by it, and what is left is what the anti-racist movement has always really been about: JOY.

The real radical hope that we share is, after all, born not of mourning but of joy. Joy in our shared neighborhoods and cities, joy in each other and our shared worlds, joy in our differences. George Floyd brought joy into the world for his family and community. So did Tony McDade. So did Breonna Taylor. So did Ahmaud Arbery. So did Tamir Rice. So did Philando Castile. So did Israel Hernandez. So did countless others who died at the hands of racialized violence. It is the end of these precious human beings’ ability to experience and share joy that we grieve. White supremacy is, at its core, a killer of human joy. Let us grieve now, together. Yes. Let us fight now, together. Yes. We do it, together, because we know the truth of human joy. We know its promise will only be fulfilled when we all have the same opportunities to reach toward it, to live in it, to inspire it in those we hold close, and those strange to us.

It’s that kind of joy that we need if we are to face this pandemic. It’s that joy we’ll need to combat climate change and ensure climate justice. It’s that joy that will help us build new and different economic models, ones that do not work only for the wealthy few, but for the very many.

Black lives matter! Scream that, from any rooftop, on any street, at any demonstration, in any argument, and see if you don’t feel some portion of the joy that’s coming as this righteous uprising continues and, I radically hope, succeeds. I vow to do the work. It will not be easy. It will not always be peaceful. Join me. That real, as yet unknown, joy we have coming is, I promise you, worth it.

On a small garden and other small gestures in the time of Covid-19

Posted: April 4, 2020 Filed under: Mishaps, Wandering in the city Leave a commentI am living in a duplex in the Little Havana neighborhood of Miami. My immediate neighbors and I share a little garden patio that faces the sidewalk. Weeks before the pandemic hit Miami, before it occurred to any of us that we’d all be living in close quarters with roommates or partners or children, and with nowhere to go, the couple next door found patio furniture to sit on. They gathered terracotta pots from local garage sales. They planted herbs: dill, basil, mint, rosemary, parsley… all flourishing now. We even have our own twin plastic pink flamingos in the yard.

In an attempt to escape the confines of my house now, I often (try to) work at a small table outside. I chat with neighbors through the chain-link fence as they pass by. They share news and jokes, local gossip. The feral cats lie together in the sun on the sidewalk and, I like to think, wonder at the quiet. Traffic in the city, notorious for gridlock, has diminished. We’re on a state-wide stay at home order as of a few days ago. A week ago, a 10pm curfew began across the city. I’ve been hunkered down for three weeks, all my classes and meetings now remote. But I’m free to sit with my partner, with whom I am vectoring, as long into the night as I like in our tiny, shared stretch of Miami.

I miss the city as I knew it just a few weeks ago. I liked to go to Coconut Grove and write at Panther Coffee, and in the evenings at Taurus, one of the oldest continuously operating bars in Miami, where patrons and bartenders really do know each other’s names. (It’s the only place in the world, really, where everyone calls me ‘Professor’).

I miss the beaches, taken from us by spring breakers whose youth made them feel invincible, I suppose, and who gathered en mass despite pleas from public health officials here and everywhere, until all those piles of warm sand, and even the salty Atlantic waters lapping at the shores, became forbidden territory.

It’s a strange thing to grieve a city still, if more quietly, humming all around you. It’s strange to grieve the smallest of physical pleasures: the shaking of hands; the un-masked smile between strangers at a distance fewer than six feet; the touching of objects, absentmindedly, in grocery stores and shops. I miss picking up a volume in a bookstore or a library that had already been leafed through by others–who knows how many? I wish a yoga instructor could press on the base of my spine and correct my posture in a pose. I wish a colleague could greet me with a hug or a kiss on the cheek. I wish a student could come and slouch in an office chair, lament a grade or beg for more time, their ungloved fingers nervously tracing the edges of my desk. I’d like to sit in the presence of people whom I do not know, in a crowded cafe, and watch the world go by on something other than the screen of my lap top. I’d like to order a meal at a restaurant, with friends, and have it set, steaming, before us by bare hands. I’d like to share food across the same table, take bites of things from other people’s plates.

May that city, that world, in some form, come back to us. Though I hope that when it does it will be a world better than the one we have been forced to leave behind, that vanished so quickly as the sickness spread. I hope that we will notice, and love, the hands that pass a dish, or count out change, or extend awaiting an offering. I hope that we will keep with us, all, the unthinkable volume of care and comfort we neglected to notice. I hope we will never forget that those many heroes of our current struggle were not made heroes by pestilence, but were heroes all along: cashiers, gas station attendants, delivery drivers, farm workers, nurses… That we will know when this is over that a handshake, indeed, any laying on of hands, is no small thing, but rather an essential performance of the wildly vast network of bonds between all of us delicate mortal creatures in our gardens, our neighborhoods, our cities, our states, our nations, our Earth.

But for now, I take great solace in the small space of the garden built by my dear neighbors. And in the walkers and joggers and their leashed dogs who pass. In the cats basking on warm concrete and licking their paws. I cook with the herbs that grow in what is now both outdoor workspace and tiny community. I ride my bike. I hope for better news, or no news at all. I wash my hands.

On Sharing

Posted: October 15, 2019 Filed under: Technology, Wandering in the city Leave a commentComrades! I neglected to post this when it was hot off the presses. But here it is, cold off the presses. Go to your local (architecture) library and find my article, co-authored with Jeff Kruth: “Buenos Aires Libre: Risk, Resistance, and Tactical Sharing,” in Plat 7.0.

Play of the Day

Posted: February 24, 2018 Filed under: Language and text, Plays of the days, Technology Leave a commentEsteemed readers. If any of you remain, given my long lapse in posting, I hope that this small offering will bring you joy. Or at least reassure you that I am among the living and that I actually do work, and even write, away from this small series of calls into the abyss of the Internet.

The play of the day is the recent publication of an article I wrote for the now in print Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature.

If you care about literature, or if you don’t but you care about me, or if you care about neither but are in support of knowledge production much more generally, get thee to a library and find this book. If nothing else, it will turn you on to an incredible collection of works worth reading.

Play of the Day

Posted: February 8, 2017 Filed under: art, Mishaps, Plays of the days, Technology Leave a commentFriends, Wizards, Comrades,

The play of the day is my most recent publication, co-authored with David Lyttle, at Fall Semester. Now available online here. This work is in the second volume of their truly wide-ranging and fantastic collection of essays on aesthetics, politics, and so much more. I’m proud to have been included as a part of their fascinating and entirely necessary, perhaps more than ever, interventions. Our essay is part of a larger project (some of which is available in the last post.)

Enjoy! Critique! Or just lock yourself in a room and practice ritual magick!

On Magick, Our Brain, and Biopolitics

Posted: January 28, 2017 Filed under: art, Language and text, Mishaps, Technology 1 Comment[Dearest readers! What follows is a.) a small gesture to those few among you who might have been hoping I would actually produce content on this long-ignored blog, and b.) a small call for resistance in a dark political night. Things are bad. But I want to continue to believe in discourse and in truth. The following paper is a small portion of a larger project I have been working on with the inimitable and absolutely magickal David Lyttle. We first delivered it at the annual meeting of the Society for the study of Literature, Science, and the Arts in Atlanta, GA in November of 2016. Enjoy! Or critique. Hopefully both.]

By David Lyttle and (yours truly) Allison Schifani

“Magick is a culture.” So writes Alan Chapman in his Advanced Magick for Beginners.* Today, we are trying to take Chapman more seriously than perhaps he took himself by looking at the rituals of Western esotericism, also known as magick, as creative technologies that may be employed to engage and shape what Catherine Malabou has called “our brain.”** And to do so for radical ends.

Malabou looks at recent developments in neuroscience to position brain plasticity not only as a material fact, but as a political opportunity. We hope to look at chaos magick, a particular contemporary version of Western esoteric ritual practice, in terms of what it can do to and with the brain in order to answer the call Malabou makes.

Malabou writes “The word plasticity […] unfolds its meaning between sculptural molding and deflagration, which is to say explosion. From this perspective, to talk plasticity of the brain means to see in it not only the creator and receiver of form but also an agency of disobedience to every constituted form, a refusal to submit to a mold.”***

Utilizing the juxtaposition of chaos magick and brain plasticity we hope to outline ways in which we might think of magick as already enacting in its practice epistemological gestures that parallel Malabou’s reading of brain plasticity. We also look to studies in neuroscience and psychology which point to magick in practice as a brain-shaping technology. Magick can provably shape the brain, we argue, yes, but it is also geared to do so in ways that do something to “our brain,” that is to say, in ways that can radically reshape the social milieu and work against capitalist productions of identity and the self.

There are a number of reasons, in any critique of capitalist productions of identity and the self, to look to magick. Western esotericism has remained countercultural, and if not ‘occult’ in the sense it perhaps once was, its wide collection of rituals, texts and epistemological structures persist in their resistance to legibility, and make magicians difficult to identify. Magick itself remains without a coherent identity. It could be said to understand itself as its own “agent of disobedience to every constituted form,” and also, just as Malabou’s plasticity, Magick “refuses to submit to a mold.”

Magick also remains counter-cultural in the sense that it is largely ignored by popular discourse (even discourse on religion or mysticism). This allows us a number of possible exploits. Our larger critical project, putting neuroscience, philosophy, and magick within the same milieu of resistant possibility, is, we hope, its own kind of magickal act.

For the purposes of this short exploration, we will be focusing on what is known as ‘chaos magick,’ rather than any number of other traditions. Although chaos magick exists primarily at the fringes of culture, it has in places had a broader cultural influence through the work of artists, writers, and musicians. For example: Genesis P-Orridge (of the bands Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV) founded an organization dedicated to magickal and artistic experimentation called the Temple Ov Psychic Youth. Comics writer Grant Morrison popularized chaos magick primarily through his series, The Invisibles, whose central plot follows a group of anarchist sorcerers conspiring to fight nefarious forces of control and domination. The writer William Burroughs (who P-Orridge describes as a “magical mentor”) became involved with chaos magick late in life as a member of the chaos magickal order known as the Illuminates of Thanateros.

The origin of chaos magick as a distinct esoteric tradition can be traced to the 1978 publication of Liber Null by the English occultist Peter Carroll. In Liber Null, Carroll proposed a paradigm of esoteric practice that did not require practitioners to use any one particular set of symbols or rituals, or to adopt any specific belief systems (supernatural or otherwise). Chaos magick adopted the skeptical, empirical approach to magick previously advocated by occultist Aleister Crowley, but went a step further by attempting to strip away obfuscating jargon, complicated symbolism, and specific metaphysical assumptions. By distilling magick to a set of simple, adaptable core principles and practices, chaos magick effectively lowered the barrier of entry to magickal practice, insisting that anyone could do magick. Chaos magick also eliminated the requirement that magicians must “believe” in any supernatural explanation for how magick works. Psychological and purely materialistic models are given equal footing with supernatural explanations, although practitioners are cautioned against dogmatically adhering to any belief system, and encouraged to entertain multiple, possibly conflicting models simultaneously. As Carroll writes,

It is a mistake to consider any belief more liberated than another. It is the possibility of change which is important. Every new form of liberation is destined to eventually become another form of enslavement for most of its adherents. […] The solution is to become omnivorous. Someone who can think, believe, or do any of a half dozen different things is more free and liberated than someone confined to only one activity.

Chaos magicians often utilize altered states of consciousness (called ‘gnosis’ in the discourse of Carroll and later writers) in conjunction with ritual and symbolic manipulation. Such states include sexual excitation, exhaustion, absorptive trance induced by meditation, hallucinatory states produced through drug use, sensory deprivation, and others. Gnosis is proposed as a means of disrupting the filtering and censoring mechanisms of the conscious, rational mind, allowing ritual and symbol to act directly on the precognitive and unconscious level.

Chaos magick is deeply invested in embodiment. And its investment, while plastic, always returns to a rootedness in the singular, experiential phenomena that can be produced by and through the body. It also ties both magical potential and liberatory capacity to the body.

(Carroll again:) There is a thing more trustworthy than all the sages, and which contains more wisdom than a great library. Your own body. It asks only for food, warmth, sex and transcendence. Transcendence, the urge to become one with something greater, is variously satisfied in love, humanitarian works, or in the artistic, scientific, or magical quests of truth. To satisfy these simple needs is liberation indeed.

The body, in this discourse, thus becomes a site of multiple potentialities. While it may be the site of care for the self, it is utilized as a way to destabilize imposed notions of care in favor of processual critiques of ‘self’ and ‘identity’ that can be accessed through physical experience. Gnosis works in part because these states of extreme experience derail the capacity of the practitioner to attach herself to a narrative of a stable ‘I.’

If we think in terms of Malabou, part of the material body on which ritual works would include, of course, the brain and the shape of our understanding of the self to which the conceptual formation of the brain is linked. But the idea that magick works on the brain need not be a metaphor for ideological critiques alone.

How do ritual practices, the focused use of language, and the various extreme states of being collectively referred to as ‘gnosis’ actually function to exploit neuroplasticity, and change the brain in measurable ways? Research addressing this question is, of course, still somewhat young, but there are several intriguing examples that hint toward the efficacy of these practices as tools for changing the brain, and by extension, the self.

Much of chaos magick involves the use of intense, focused attention, and the practice of meditation is considered a foundational tool for cultivating the ability to direct one’s attention. Meditation is perhaps the most well studied example of how embodied ritual practices can change both the functionality and physical structure of the brain. Numerous studies of experienced meditators (typically Buddhist monks with years of training), have shown that this practice changes the brain at both the functional level (brain wave activity as measured by EEG, functional connectivity as measured by FMRI) and the structural level (marked differences in cortical thickness in several regions, specifically those associated with emotional regulation, bodily awareness, and cross-hemispheric communication). Furthermore, the effects of meditative practices on the brain can manifest in a relatively short time: one study demonstrated that just 11 hours of meditation can induce measurable changes in brain structure in novice meditators.

Other methods for producing gnosis include the use of psychoactive drugs, a practice directly advocated by many in the chaos tradition and in western esotericism more broadly. Earlier this year, scientists released the first modern brain scans of patients who had volunteered to take LSD, among other hallucinogenic drugs. According to The Guardian’s summary of these studies:

The brain scans revealed that trippers experienced images through information drawn from many parts of their brains, and not just the visual cortex at the back of the head that normally processes visual information. Under the drug, regions once segregated spoke to one another.

Further images showed that other brain regions that usually form a network became more separated in a change that accompanied users’ feelings of oneness with the world, a loss of personal identity called “ego dissolution.”

And, of course, one of the central goals of gnostic ritual is the dissolution of a stable ‘self.’

Malabou’s own exploration of neuroscientific discourse is also deeply invested, if not in ‘ego-dissolution’, certainly in the implications of brain plasticity in terms of the possibility of gesturing toward the other by means of understanding our own material selves as plastic. Hers is a vision of plasticity that extends from the brain to its milieu–not just its body, or its environment, but its world.

In addition to the use of gnosis, chaos magick relies heavily upon the strategic use of language, rigorous self-analysis, and the manipulation of symbols to disrupt and alter existing patterns of perception, thought and behavior. Many of these techniques are similar to those used in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The underlying premise of CBT is that upsetting emotions arise due to distorted patterns of thought and self-talk, and the treatment process consists of systematically disrupting these patterns and replacing them with new, more adaptive ones. CBT is one of the most successful and empirically-supported types of (non-pharmaceutical) psychological treatment in use today. Moreover, recent research has suggested that CBT, like meditation, can produce measurable changes in brain function and structure. Collectively, these results suggest that language, focused thought, and self-interrogation can indeed change the brain in lasting ways.

Certain practices within chaos magick can be seen as a sort of intense, D.I.Y. variant of CBT, in the sense that they serve to systematically uproot and replace patterns of thought, speech and action. However, there is a crucial difference: CBT, like many forms of psychotherapy, is designed to make patients more “functional” and able to cope within the broader social, political, and cultural frameworks in which they exist, without challenging those same frameworks, or implicating them as potential sources of the patient’s suffering. In contrast, magickal practice, rather than simply helping practitioners better navigate existing power structures, encourages critical engagement with the self and the broader structures in which the self is embedded. In Malabou’s terms, CBT proposes a model of flexibility, where magick seeks plasticity.

One potential pitfall of reading magick as a technology of resistance (even if that resistance leverages brain plasticity) is that capital produces itself as a magical. Melinda Cooper has called capital ‘delirious’ but this is a critical language that could just as easily be reframed in occult terms.+ What is the ‘invisible hand’ of the market if not an occult force? And its modes of abstraction and speculation also seem to be squarely within the category of magic. Not to mention symbol manipulation, the central component of magickal ritual practice. Ideological structures of contemporary capital remain bound tightly to the symbolic. This said, to think of resistant technologies in terms of magick is both novel (especially when we put magick in conversation with brain plasticity) and ‘old hat’: many of the resistant projects of the 20th and 21st centuries have appropriated capital’s magical logic. What this means is that both plasticity and magick are ambivalent in their relationship to the larger structures in which they operate. They can be leveraged for or against the status quo.

And if magick does not directly engage, or even care, about its impacts on the material brains of practitioners, its aim is certainly one of material change more broadly, and material change through individual and collective practice which can thus move on to change to directly shape the world.

Malabou writes:

To cancel the fluxes, to lower the self-controlling guard, to accept exploding from time to time: this is what we should do with our brain. It is time to remember that some explosions are not in fact terrorist — explosions of rage, for example. Perhaps we ought to relearn how to enrage ourselves, to explode against a certain culture of docility, of amenity, of the effacement of all conflict even as we live in a state of permanent war. It is not because the struggle has changed form, it is not because it is no longer possible to fight a boss, owner, or father that there is no struggle to wage against exploitation. To ask ‘what should we do with our brain?’ is above all to visualize the possibility of saying no to an afflicting economic, political, and mediatic culture that celebrates only the triumph of flexibility, blessing obedient individuals who have no greater merit than that of knowing how to bow their heads with a smile.++

Chaos Magick, if it does nothing else, positions itself and its practitioners as open to the explosion. It is firmly anti-docility and vocally against the effacement of conflict. In other words, when practiced radically, magick is plastic. And the way it utilizes plasticity means that it might also help us to more sustainably and equitably use our plastic brains.

____________________________________________________________________________

*Alan Chapman, Advanced Magick for Beginners, London: Aeon Books, 2008, pg. 18.

**Catherine Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain? Trans. Sebastian Rand, New York: Fordham University Press, 2008.

***Malabou, pg. 6.

+Melinda Cooper, Life as surplus: Biotechnology and Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era, Seattle: U of Washington Press, 2008.

++Malabou, pg. 79.

Of the everglades and the fiction of solid ground

Posted: March 15, 2016 Filed under: Mishaps, Wandering in the city Leave a comment

I had the great pleasure of hosting a few nature-loving friends over the course of last week. Aside from the lizard and bird-spotting you can do pretty much anywhere in Miami, we also managed to head out for a day to the 15 mile bike loop in Everglades National Park, Shark Valley.

The ride is flat and easy. The glades engulf you as you trek further along. If you’re lucky (as we were), and it’s not too trafficked, you can ride for miles with only the local wildlife as company.

The alligator population is such that sometimes you actually have to swerve to avoid the creatures as they nap—their long, dark bodies sprawled half along the pavement, half dipped in the still waters alongside it. I lost count of the number of these odd beasts we spotted somewhere in the low twenties.*

The landscape is also, of course, dense with a wide variety of strange wetland flora as well. It makes for an expansive and alien environment for a desert creature like me. And beautiful.

I spent much of the ride thinking about two things: 1.) The impending flooding of Miami and its surrounding areas, which will, you can be sure, eventually make painfully clear the consequences of our shared disavowal of climate change, and 2.), the reminder a friend recently gave me that the outline of Florida you see on any given map is a fiction. The borders are porous in the state. Land is sometimes dry and sometimes wet. The water level, not the cartographer, marks the shifting outlines of this bizarre jutting mass, a sort of vestigial tail of the continental U.S.

Much has been written about the (political) trouble with maps.** But to my knowledge, considerably less so about the ecological consequences of ordering space cartographically. If we understand Florida as solid ground to stand on, we do so in part because we believe in the fictive representation of its borders on the maps we make of it. And that representation in turn allows us to ignore the material facts of ecology, and of our participation in it. Maps also, I think, quite likely aid in the disavowal of the material facts of the State.*** These are not separate issues. And their mutual imbrication will be made only more clear when refugees cross borders to escape ecological disaster just as frequently as they currently do by cause of political catastrophe.

Riding through the glades, despite the tourists and the paved path, is one way to encourage a different kind of map making: one more rooted in the body and the experience of place (both very messy affairs) than the ordered work of dividing land from water, self from other, us from them. It seems that we will certainly, in the coming years, need better ways to make alternative maps. Because the water is coming. And we might have been better off if we had acknowledged that it has always, in some way, already been here.

_________________________________________________

* We also saw a female crocodile (apparently the only one typically in the park). And, of course, birds of various sorts flew alongside us as we rode.

**See, in particular, the lovely work of Michel de Certeau.

*** Think, for example, of the recent claims made by presidential hopeful (and all around asshole) Donald Trump about the necessity of a literal wall along the U.S./Mexico border.